Published in “Shooting Illustrated” June 2007

Published in “Shooting Illustrated” June 2007At the age of seven it became apparent that I was destined for a lifelong love affair with firearms. There would be other even greater loves in my life, but my interest in guns has never faltered and remains a dominant force these many decades later. For almost that entire time, my focus has been on recreational rather than tactical uses of guns. Unfortunately, the world is not as safe or friendly a place as it used to be. As a younger man. I kept a loaded handgun in the house, but unless there was some kind of civil disturbance or unrest underway, I rarely risked breaking the law by carrying a handgun in my vehicle. Today, many citizens believe quick access to a self-defense firearm is nothing more than good, common sense.

In the mid-’80s, Florida enacted the greatest piece of firearms legislation since the Second Amendment. That state made it crystal clear that no one could deny an honest citizen the right to carry a concealed weapon. Many states followed Florida’s lead with similar laws, including those recognizing concealed-carry permits from other states. The majority of states now have “shall issue” laws, while others that have not passed such legislation still have provisions for their citizens to be granted concealed-carry permits.

It may come as a surprise to many shooters to know that in California it is still possible to obtain a concealed-carry permit, depending on where you live in the state. This apparent contradiction of California’s anti-gun law reputation exists because permit approval is left to the discretion of the applicant’s senior local law enforcement official. If you live in Los Angeles or San Francisco, don’t bother applying. Those bastions of personal security and welfare simply don’t grant permits to average citizens. But in many communities and counties, permits are issued to citizens who have presented a viable reason to carry, attended mandatory training and passed the required tests. It’s not as good as a “shall issue” environment, but it’s far better than a “won’t issue” state.

Fortunately, I live in a California county whose sheriff ran for office promising to make concealed-carry permits available to us common folk, and to date he has kept that promise. I’ve submitted an application for a concealed-carry permit, and in the process have encountered the kind of dilemma a gun writer dreams of. California allows a maximum of three guns to be listed on the permit, and the bearer of it is prohibited from carrying any gun not listed. For years I have avoided the classic “if I could only have one gun” dialog. But if I were allowed to choose three guns, maybe I could get through the exercise and generate only a minimal amount of hate mail.

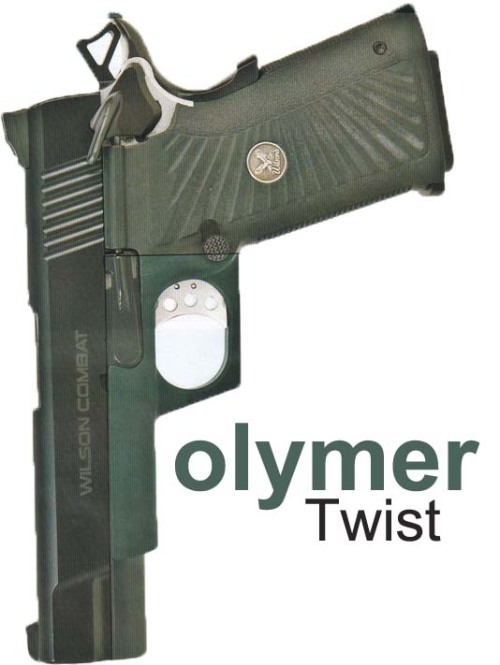

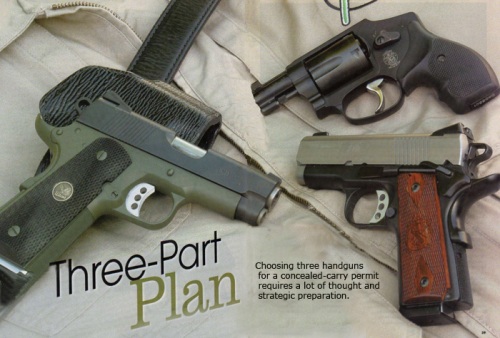

Proven design and a record of superb stopping power gives the Wilson Combat CQB in .45 ACP high credentials as a primary concealed-carry pistol. A slightly shorter 4-inch barrel makes it easier to carry than the standard 5-inch barrel of a full-size 1911.

Concealed Considerations

An immediate thought was to pick the “best” gun and follow that up by choosing two almost identical guns for backup. This would ensure I always had the optimum gun available regardless of possible downtime for such mundane things as repairs or modifications to the primary firearm. There would be no retraining on handling procedures when switching guns, and I could use the same accessory gear no matter what gun I carried. I mulled this strategy over for some time because it made a great deal of sense and offered a solution with the utmost simplicity. It also defined the type of firearm I would carry, because if there would only be one kind of gun, it would be the one with which I am most familiar and proficient. That meant I would have three 1911s in various configurations and sizes, which wouldn’t be a bad thing. But ultimately I discarded this approach, thinking that since this would be a concealed-carry gun. there would be situations and dress codes that might suggest a different firearm in order to maximize concealment and carrying comfort.

This change in approach made it easier to choose the type of gun that would be number two on the license. With some kind of 1911 as number one. the second choice would be a pocket pistol of the utmost simplicity. It could be carried anywhere on my person for a reasonable period of time without fear of discharge and would function with absolute reliability simply by pulling the trigger and if there was a failure to fire, another pull of the trigger would be all that was required. You’ve probably guessed that I’m talking about a small-frame revolver, with only the model and caliber to be determined.

My thoughts on the third gun didn’t start to gel until I took one of the training classes that California mandates in order to obtain the permit. My instructor was Bill Murphy, an active-duty California police officer and head of the SureFire Institute’s low-light training program. He did not tell the students what gun they should carry, but he strongly advised our alternate guns function the same way as the primary firearm with which we trained. Murphy’s key message was that during moments of stress we do not rise to new levels of performance, rather we revert to our basic training. If you trained with a Glock or Springfield Armory XD. for example, and had to deal with an emergency using a gun with an external safety, you would probably forget to deactivate the safety and try to fire just by pulling the trigger, because that was how you had trained. Such an error, however short lived, could prove fatal. It became clear my third gun would have to be a 1911. but probably tailored to different circumstances than my primary.

Number 1 Gun

More than a year ago. I wrote an article on Wilson Combat’s CQB entitled “The Perfect IDPA Pistol” (November 2005) in which I stated the CQB would make an excellent concealed-carry handgun. The CQB became my pick for the first and primary handgun on my concealed-carry permit, and while no man ever needs to defend his choice of a Wilson Combat pistol for his self-defense gun. I will review some of my thinking during the original evaluation.

This pistol was absolutely reliable, first shot, every shot, regardless of the ammo I used. Its barrel is 4 inches long, and it’s 5.4 inches high, making it easier to hide than a full-size 1911. However, since the gun is steel it is not unpleasant to shoot serious self-defense loads.

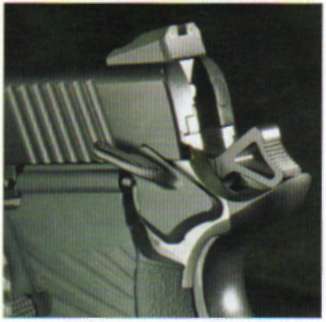

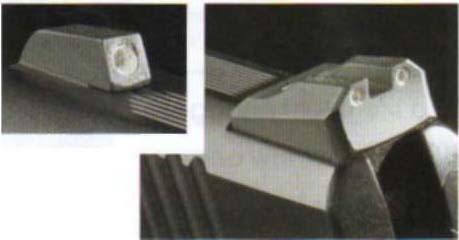

The CQB has excellent, fixed Combat Pyramid sights with tritium inserts, and all sharp edges have been rounded and smoothed. Its trigger is a crisp and repeatable 4 1/2 pounds. Though the colors are not particularly important, the Armor-Tuff finish does protect the OD green frame and black slide from corrosion. The feed ramp is polished, the barrel is throated, the frontstrap and flat main spring housing are checkered, and the magazine well is beveled. There is a high-ride beavertail grip safety and an extended tactical ejector.

Wilson offers two magazine sizes, a feature I particularly like. The standard seven-round magazine fits almost flush, while the eight-round spare magazine extends slightly below the grip frame. This allows concealed carry of the gun with eight rounds (seven in the magazine and one up the spout), and provides eight more in each tucked-away backup magazine.

While shooting three Black Hills .45 ACP jacketed hollow point loads (185, 200 and 230 grains), the lighter bullets printed dead-on at 25 yards and the 230-grain slugs hit about an inch left. I’d call that street-ready.

Backup Made Better

Smith & Wesson's Model 442 (right) weighs just 3 ounces more than the company's Model 340PD and is nearly half the price of the top-tier .357 Magnum. The author plowed that savings into an XS Big Dot front sight, along with some refinements and an action job from Cylinder 8 Slide.

Nothing is as inherently reliable as a revolver, and while I normally prefer the large-frame magnums, concealed carry dictates something smaller. Since this was to be the go-in-any-pocket gun. and therefore would not be supported by a belt or other type of body harness, lightweight was the order of the day. Smith & Wesson makes some very light snub-nose revolvers, and then it makes some insanely light snub-nose revolvers. I say “insanely light” because when you touch off a full-house .357 Magnum in an 12-ounce scandium-frame revolver, you’ll start thinking only an insane person would do such a thing. In a moment of stress you might not immediately notice how painful the recoil is. but you will during practice sessions. Even if you minimize your practice. California requires that permit holders shoot 75 rounds through each handgun listed on the permit. I’m a big believer in handgun practice, so selecting the revolver and caliber required some serious thought.

Since this was a pocket gun. I wanted a hammerless model. The Smith & Wesson website shows two interesting candidates. One is the top-of-the-line Model 340PD. a scandium-frame .357 Magnum weighing 12 ounces. The other is the Model 442, an aluminum-frame .38 Special weighing 15 ounces. That’s not much difference in weight, but you can feel it when holding the gun in your hand or in your pocket. I’m not sure if the extra few ounces would make a difference in firing .357 Magnum loads, since the slightly heavier gun is rated for .38 +P. not .357. The real noticeable difference is in the price, with the scandium .357 retailing for several hundred dollars more than the aluminum .38. I made a decision and sent the Model 442 off to Bill Laughridge at Cylinder & Slide to work his magic.

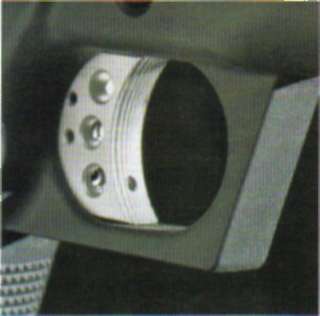

The fixed sights on a snub-nose revolver are rudimentary at best. Even with the red insert in the front blade of the Model 340PD. I could barely see the sights in daylight. I couldn”t see anything in low light. The first change Laughridge made was to install an XS Sight Systems Big Dot Tritium front sight on the Model 442. Given the minimal space at the rear of the topstrap and shallow trough that was the rear sight. Laughridge rounded out the channel so the Big Dot nestled nicely into the enlarged half-moon notch. Without my shooting glasses nothing was clearly in focus, but I could see the large white ball in daylight and the glowing tritium in darkness. I wasn’t ready to take the little gun squirrel hunting, but I was definitely a force to be reckoned with even in low-light conditions.

Laughridge added some other nice touches that should prove useful, such as chamfering the rear edges of the cylinder’s chambers, polishing the trigger and tuning the action. My first thought in looking at the finished Model 442 was the vertical face of the front sight would be prone to catch the tight edge of the front trouser pocket during the draw. While true, I think this is a non-issue since it only happens in small pockets on tight pants like jeans, and when the pocket is that small and tight. I have trouble getting the gun and my hand in and out of the pocket. With more realistic clothing it is fine, and besides, ramped front sight blades frequently have serrations that can snag clothing as well. Eliminating the front sight would alleviate the problem, but in a situation warranting the use of a concealable firearm. 1 want to see something at the front end of that barrel.

When wearing a holster just isn't practical. Smith & Wesson's Model 442 in .38 Special is an effective alternative to going unarmed. Its simple operation and reliability, combined with the shrouded hammer and light weight, allow it to be carried unobtrusively in a coat or cargo pants pocket.

Last But Not Least

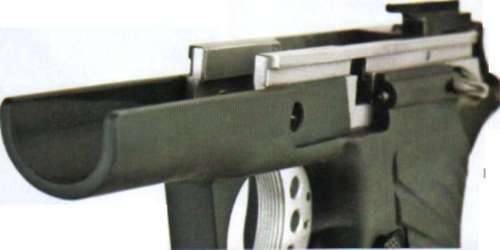

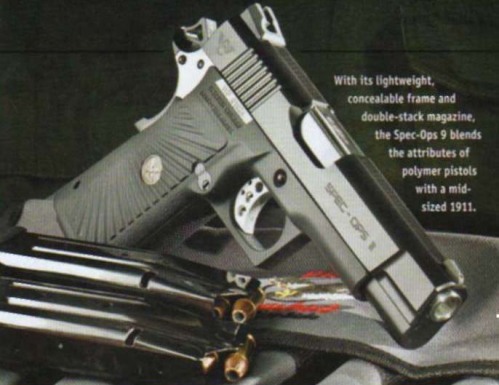

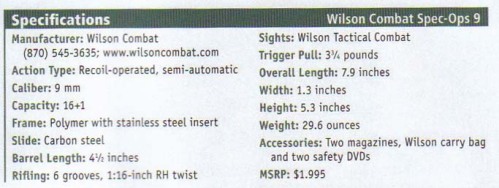

Picking the third gun was even more difficult than the second. I decided it would be another semi-auto, and based upon Murphy’s Law (the good one learned in class), it would have to be a 1911. However. I wanted something a little smaller than the CQB for slightly-easier concealment and a little lighter for more comfort during prolonged carry. This meant I needed a pistol with a shorter barrel than the one on the Wilson and an alloy rather than steel frame.

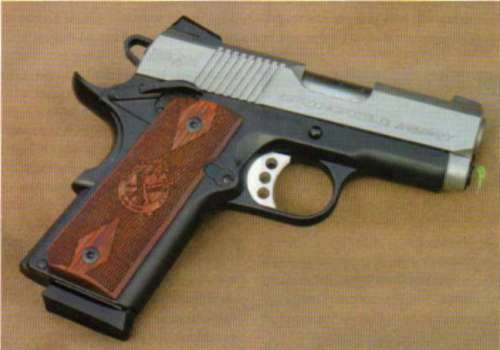

I recently spent some time with a pair of little 1911s from Kimber and Springfield Armory and was very impressed with the offerings of both companies. In the March 2007 issue

I reviewed Kimber’s Aegis and Springfield Armory’s EMP, both in 9 mm. Ordinarily I would have selected a .45-caliber micro compact for my third concealed-carry gun. but those pistols opened my mind to the world of mini-nines. They are easier to shoot than a comparably sized .45. Since they’re 1911s, all the controls are the same. If I suffered some kind of injury that forced me to shoot with the weak hand, I would do much better with a 9 mm than a .45. Finally, if I found myself in a life-threatening situation, the outcome of which depended on one of the women in my family picking up my carry gun. I think our safety would be better served by a more manageable, less intimidating 9 mm.

Springfield Armory's Enhanced Micro Pistol (EMP) in 9 mm takes the final spot on the author's California concealed-carry permit. The ability to carry as many as 27 rounds of 9 mm ammunition should make him relatively comfortable when venturing into the urban wilderness.

For now. I plan to list the Springfield Armory EMP as the third gun on my permit. The differences between the EMP and Aegis are small, but the EMP does have an ambidextrous safety, making it easier to operate with the weak hand. Its magazine carries one more round than the Aegis (nine versus eight), and its frame is slightly shorter.

I’m familiar with the arguments regarding stopping power of the .45 versus that of 9 mm. which is why the .45-caliber CQB is my primary gun. Likewise, the .38 Special gives up something to the .357 Magnum, but as always, measuring or calculating stopping power requires a hit rather than just a very loud miss. Perhaps a heavier weight .357 Magnum snubbie might be better for the number two gun, allowing me to use .38 Special loads for practice while carrying magnum loads on the streets.

During the next year. I may change my mind about what guns I want on my concealed-carry permit, and the good news is that for a few bucks and a short qualification session using the new gun, firearms listed on an individual’s permit can be changed in California. What I am comfortable with is the XS sight on the front end of that little barrel. In fact I might put an XS sight on the third gun. and as long as I don’t change firearms, this would not require any modifications to my permit. As always, more low-light practice sessions are in order, particularly since cockroaches rarely come out to dine in bright light.

Another Option

S ince I started this project. Smith & Wesson introduced a new snub-nose revolver that has some of the custom touches Cylinder & Slide made to my Model 442. It’s the Model M&P 340, and at a weight halfway between my two prior options (13.3 ounces) it’s worth a look. Meanwhile, if any of you aging warriors with dimming vision have a snub nose on which you might someday bet your life, you might want to give Bill Laughridge at Cylinder & Slide a call.

Cylinder & Slide

Smith & Wesson

Springfield Armory

Wilson Combat & Scattergun Technologies