Published in “Shooting Illustrated” May 20

When Federal announced the new .327 Fed. Mag.,

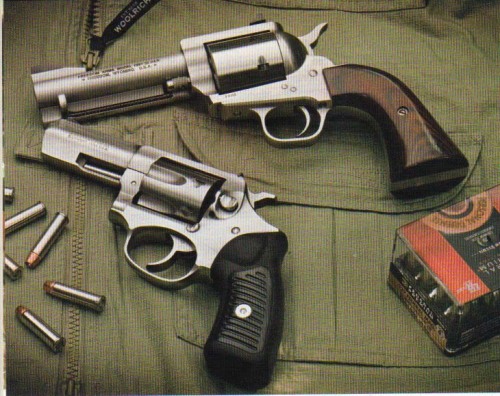

Ruger responded first with its SP101

The theory was to offer some serious power in a compact self-defense handgun for recoil-sensitive shooters. Having known a couple of folks who were recoil sensitive, yet were interested in a firearm for self-protection, the gun-and-caliber combination made sense to me.

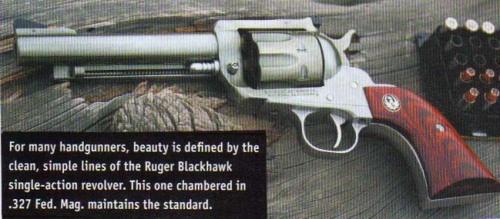

A respected gun-writer friend suggested Ruger chamber the new round in a larger-frame revolver, particularly the Blackhawk. Having been so impressed with the .327 Fed. Mag.’s performance when it first came out, I thought this was a great idea, but I didn’t really expect to see it happen. To my delight, Ruger is offering the hot cartridge in both its single-action Blackhawk and its double-action GP100 revolvers. And I can see justifiable applications for both.

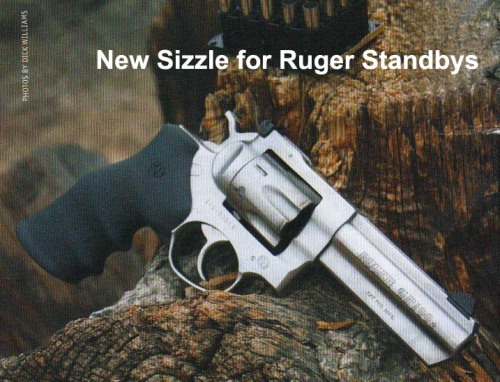

Ruger's GP100 chambered in .327 Fed. Mag. is a big, tough gun whether intended for home defense or outdoor use. The asymmetric look of a seven-shot revolver has been known to shock old-time gun writers, but that extra round is universally accepted as a good thing.

The new .327s are from Ruger’s stainless steel stable of revolvers. The GP100 has a 4-inch barrel, but one big surprise is its cylinder holds seven rounds. The extra round is made possible by the GPlOO’s frame being beefier than that of most mid-size revolvers.

When it comes to self-defense, more rounds are better. For the millions of Americans who keep a gun for home defense, but don’t carry concealed, there is no need for a small revolver. Your nightstand doesn’t care what the gun weighs, and your practice sessions will be much more pleasant with a larger-frame gun. Self-defense isn’t about having fun, but enjoying training sessions is better than dreading them and will translate to greater proficiency with your gun.

The GP100 also comes with Hogue’s finger-groove rubber grips, which happen to fit my hand perfectly. Although the .327’s recoil doesn’t necessitate soft grips, I’d keep them because of the excellent ergonomics. If the gun doesn’t fit your hand as well as it does mine, you might have to look at different grips.

Not much is simpler than a basic double-action revolver. No manual of arms is required for presentation or preparation; simply aim and pull the trigger. If, for any reason, a round doesn’t go bang, pull the trigger again. Speaking of just pulling the trigger, I was more than happy with the smooth, double-action trigger on the GP100. In a defensive scenario, shooting double action is simple and effective.

Admittedly, a revolver is slower to reload than a semi-auto, but when fully loaded, the GP100 gives you seven opportunities to solve the problem. And how many of us with semi-automatics in our nightstands put a spare magazine in a pocket when we pick up our gun in response to a bump in the darkness? Please don’t tell me you wear a spare magazine carrier to bed. I’m not saying we should surrender our semi-autos for a wheel gun in .327 Fed. Mag. However, I am saying there’s a self-defense role for the GP100 in many homes.

Given my boyhood love affair with a Ruger Single Six, it was the Blackhawk in .327 that really got my attention. For this offering, Ruger chose stainless steel and a 5 1/2inch barrel. If sales warrant, we’ll probably see it in blue and with other barrel lengths in the future.

Prepare for a shock when you see the eight chambers in the Blackhawk cylinder. Other than the increased capacity, the rest of the gun is classic Blackhawk with wood grips and adjustable black sights. If you were a kid west of Rhode Island, your first centerfire handgun was probably a Ruger Blackhawk. And if you’re old enough, to this day you know that with a centerfire Blackhawk revolver within reach, you will not be someone’s prey.

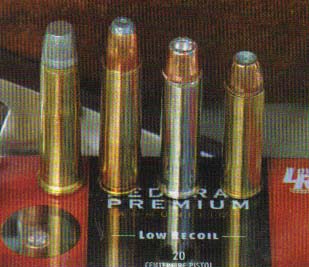

I found the .327 Fed. Mag.’s performance very impressive, particularly in normal-length barrels. Federal’s 85-grain Hydra-Shoks generated right at 1,600 fps from the Blackhawk’s 5 1/2-inch barrel and just more than 1,580 fps in the GPlOO’s 4-inch barrel. At 25 yards with my wrists on a rest, groups ran slightly over 2 inches from the Blackhawk and a little more than 3 inches in the GP100. Black Hills 85-grain .32 H&R Mag. gave 1,158 fps in the Blackhawk and 990 fps in the GP100. Groups were just a little more than 2 inches in the Blackhawk and just less than 2 inches in the GP. I had only one box of Federal 100-grain jacketed soft points and wanted them for a javelina hunt, so I just tested them in the Blackhawk. Results were velocities around 1,530 fps and groups around 1 1/2 inches.

One of my favorite hunting pastimes is chasing rabbits with handguns, and the new .327 Blackhawk looks like a perfect small-game gun (with self-defense capabilities included) for bumming about Arizona’s high country and game-rich deserts. It would also make an excellent trail gun.

I should comment about the sights on the revolvers. Both have black front blades and black, adjustable rear sights. The only difference is the GP100 has a white line around the rear-sight notch. It’s easier to see the rear sight in dim light or against a dark target, but it’s not the rear sight at which you should be looking. For daylight hunting, I find plain black sights seem to work best. For defensive shooting, particularly up close, it’s the front sight that needs to be seen, not the rear. Both guns should be fine as equipped for hunting, unless the angle of the sun is such that the white outline catches the glare and washes out your sight picture. But that’s just my opinion, and if your vision is better than mine, you might have a different preference.

It will be interesting to see how the .327 Fed. Mag. fares in the marketplace. The cartridge doesn’t really do anything the .32-20 Win. or .30 Carbine won’t do in a medium- to large-size handgun. But, the .327 is a more compact cartridge and will work in a small-frame revolver. It’s also available with a greater variety of high-performance ammo than either the .32-20 Win. or .30 Carbine and will prove easier to reload than the tapered .32-20 Win. case or rimless .30 Carbine. In any case, several gun manufacturers and a large ammunition company are sinking some resources into the new caliber. The rest is up to us shooters.