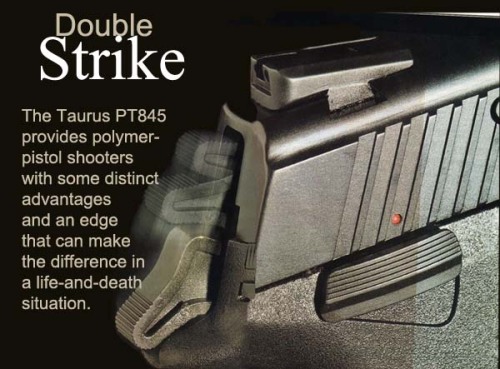

As published in “Shooting Illustrated, January 2009

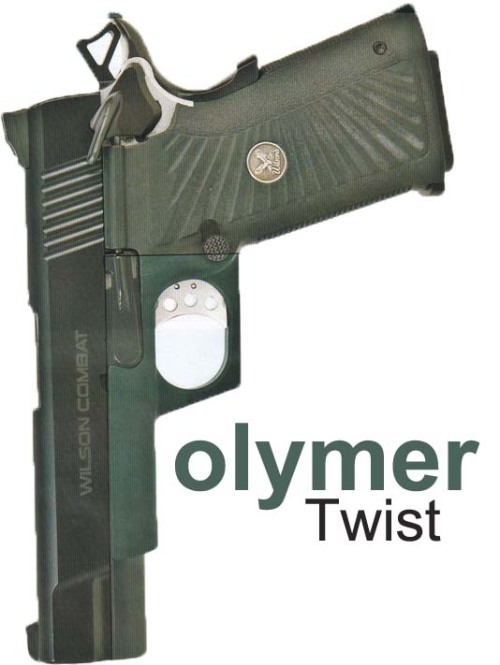

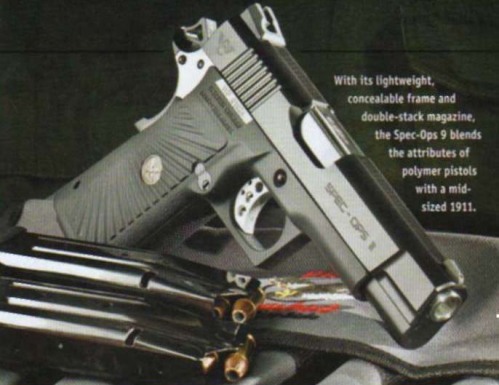

It’s tough for an old dog to wax eloquent about a new polymer-frame handgun. I grew up with guns made of blued steel, later accepting stainless versions because I had become slothful and lazy about cleaning hardware after a day’s shooting or a few days in a hunting camp. It look me longer to accept lighter-weight handguns made of aluminum and other exotic materials, but at least they were made of metal.

I still struggle with the polymer-gun concept simply because the gun doesn’t Feel the way a gun should Feel, and because it doesn’t seem intuitively right for a gun to

flex when fired. All that said, I became a “born again” believer in lightweight handguns when I obtained my CCW permit and began venturing out while trying to keep a handgun hidden somewhere under my clothing or in a trouser pocket. And one of the more affordablc materials that can be used to achieve weight reduction is polymer.

The pistol comes with two, 12-round magazines and a handy loading tool, which makes prerange preparations more pleasant.

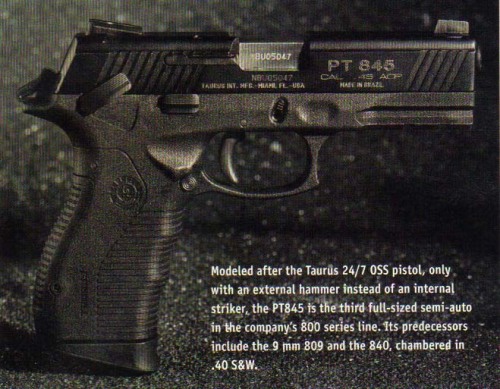

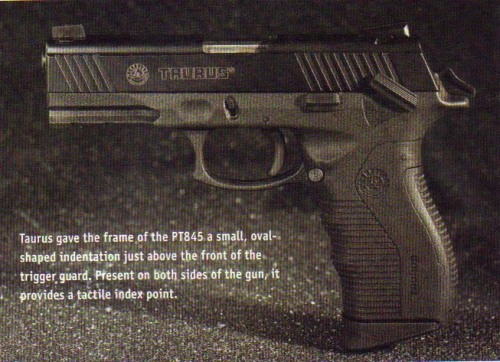

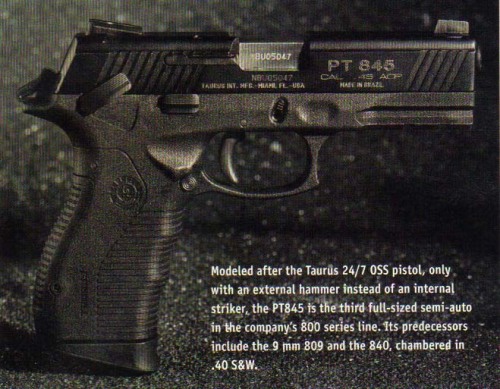

At first glance, Taurus’ new PT845 doesn’t look much different than other polymer-frame handguns on the market. It’s chambered in .45 ACP and has a double-stack magazine with a capacity of 12 rounds. For those of you who don’t enjoy loading wide-body magazines, be aware that the Taurus box contains a magazine-loading tool along with two magazines. The magazines have two witness holes with the numbers 6 and 12 in their right side to indicate how many rounds you have loaded. The magazines have extended bumpers that provide a finger rest to facilitate slapping loaded magazines into the gun and protect the magazine when it hits the ground during a speed reload. Other items delivered with the gun include two additional, different size backstraps that allow you to change the shape and feel of the grip, a nylon bore brush for those of you with a cleaning fetish and the Taurus key set for operating the internal safety lock.

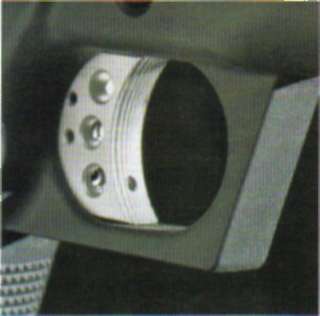

Interchangeable backstraps allow PT845 users to find the best fit for their hand size. The pistol comes complete with three different sized options, making the pistol tailorable, right out of the box.

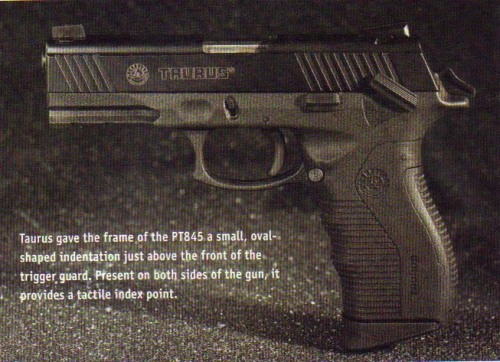

The frame is made of a hard polymer: there’s nothing soft or squishy about the feel of the 845 grips, unlike those on some of Taurus’ revolvers that are designed to absorb recoil. There are ridges running laterally around the grip that provide some surface roughness for grip control, plus there are vertical cuts in the ridges at the front and rear of the grip frame for additional roughness. Polymer-frame .45s do tend to jump around a bit. and these measures did help in controlling the gun during strings of rapid fire.

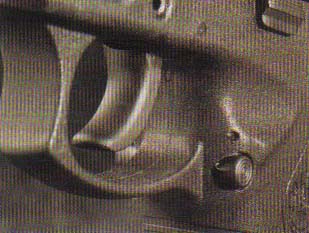

What really got my attention on the frame was the ambidextrous set of controls that accommodated righties and lefties equally well. The safety lever, decocking lever, slide-release lever and magazine-release buttons were in exactly the same position on each side of the gun and were mirror images of each other in terms of how they functioned. I could operate the slide release latch and the safety lever without changing my grip position. It required a slight rotation of either hand to hit the magazine-release button, but the movement was minimal. I wasn’t nearly as smooth running the controls with my left hand as with my right, but that’s to be expected.

A major advantage of the polymer framed pistol is the ease with which an integral rail can be molded into the gun's body. The Pt845 has such a rail, which makes mounting a laser or a light a snap, quite leterally.

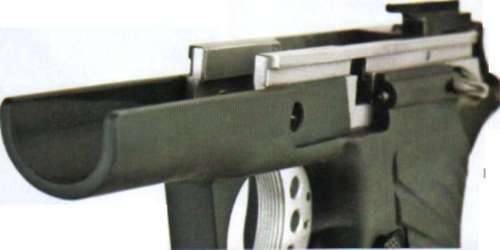

There is a Picattiny accessory rail on the front of the frame for mounting your flashlight. Given the number of gunfights that take place in low-light conditions, this is an excellent feature on any defensive handgun. A disassembly latch protrudes from the frame on both sides, and both ends must be depressed to remove the slide from the frame. A bit of dexterity is required, but since I mastered it in less than 10 seconds, I consider the 845 an easy gun to take down.

Serrations in the steel slide offer positive purchase when clearing malfunctions or performing a chamber check. The safety lever also functions a a decocking device.

The slide is steel and has serrations both front and rear to facilitate manual operation in the event of a malfunction or chamber check. In the upper edge of the external extractor is a thin piece of metal that functions as a loaded chamber indicator. Normally, this piece lies flush with the extractor and slide, but when a cartridge is in the chamber and the rim under the extractor, the indicator protrudes slightly out from the surface of the slide. In bright light, you may be able to see the strip of red that appears, and if you have the sensitive fingers of a safecracker, you might feel the slightly protruding indicator. In dim light. I could not see the red, nor did a tactile check assure me of the gun’s condition. The good news is that the slide serrations and overall ergonomics make a manual chamber check of the 845 a simple and quick task.

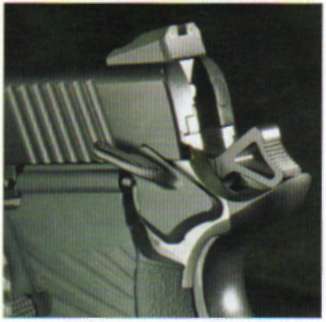

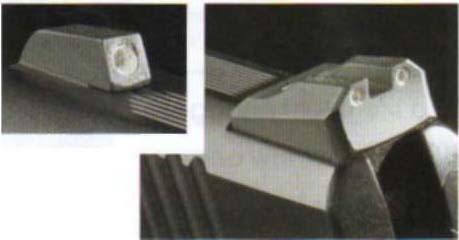

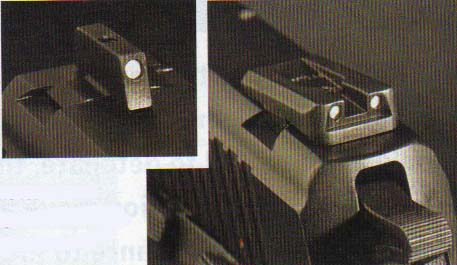

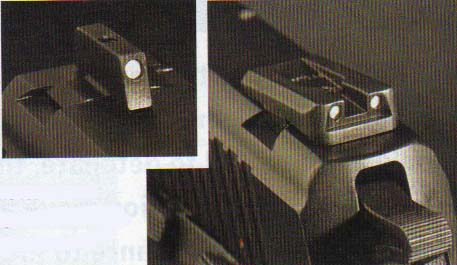

Novak sights provide a great benefit to shooters. They are easy to see and offer quick target acquisition, even in high-pressure situations. Both sights are dovetailed into the slide for windage adjustment and the rear offers elevation changes as well. They are the author's favorite feature on the PT845.

The 845’s sights are Novaks, and they are superb. In fact, they are my favorite feature on the 845. being easy to see and seemingly quicker to acquire than any other sights I’ve used lately.

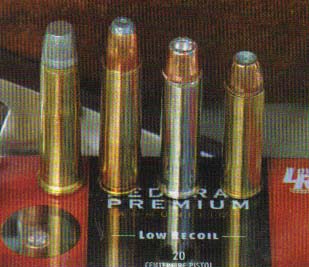

The ratio of rear sight width to from sight width is such that lots of light shows on both sides of the blade. Both front and rear sights are mounted in large dovetail slots with setscrews that allow adjustment for windage. They were dialed in perfectly with Black Hills 230-grain jacketed hollow points when I received the gun. and when I switched to the lighter-weight frangible Remington and TTI ammunition, there was no noticeable change in point of impact between the 7 to 15 yard ranges at which I did my testing.

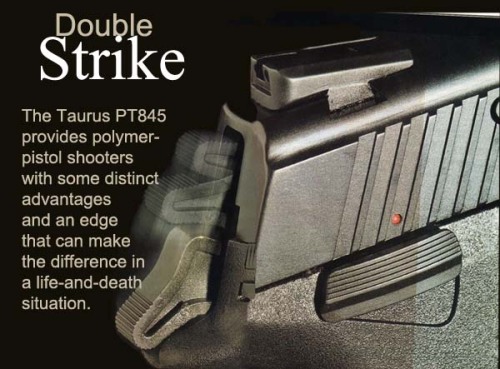

Unlike the Taurus OSS, on which the Model 845 was modeled, the 845 has an external hammer. Unlike the 1911, the 845 can be fired double action with the hammer down in addition to allowing single-action firing with the hammer back. And while the 845 has an external, manually operated safety, it also has an internal firing pin block that won’t allow the gun to fire unless the trigger is in the rearmost position.

The PT845's trigger had a single-action pull weight that averaged 3 3/4 pounds. In double-action mode, the pull weight was a few ounces shy of 10 pounds.

At first this sounds like it might be a more complicated arrangement than you would want on a defensive pistol, but take a second look before deciding. With a round in the chamber, you can fire the gun with the hammer cocked or down as long as the safety lever is not in the up position. Push the safety down with the thumb of your shooting hand, just like a 1911, and a short pull of the trigger fires the weapon. Push the safety lever too far down and the hammer falls harmlessly to the double-action firing position, which then requires a long pull on the trigger to fire the weapon. When the slide cycles after a shot, the hammer returns to the cocked position, which puts the gun back in single-action (short trigger pull) firing mode. If you have issues carrying cocked and locked, you can carry hammer down with the manual safety on or off.

The Taurus 845 has the same "Strike Two" capability as found on the company's 24/7 lineup. Should a primer fail to detonate, the trigger resets to the double-action mode and the shooter has a second chance to fire the round.

The Taurus 845 has the same “Strike Two” capability as found on the company’s 24/7 lineup. Should a primer fail to detonate, the trigger resets to the double-action mode and the shooter has a second chance to fire.

One other feature I like is the hammer’s shape; I can thumb the hammer back with the shooting hand much more easily than I can perform the same function on a 1911. It’s not as natural as on a single-action revolver, but a much smoother maneuver than any other semi-auto pistol I can recall. This feature may mean more to me than it would to you because I had some difficulty in firing the 845 double-action from the hammer-down position—more on that later.

The initial range trip was more fun than expected simply because I had the Taurus magazine loading tool. It’s a small thing, perhaps, but it did start the day right. There was only one problem with the hardware, and I might have been the cause. One of the two furnished magazines failed to drop clear of the mag well when the release button was pushed. It dropped about half way and stopped, whereas the other magazine fell clear. It was easy to strip the stuck magazine clear of the pistol with the reloading hand, which is not a bad exercise to practice since Murphy’s Law says this will only ever happen at the worst possible time. Since the other magazine worked perfectly, it was obvious something was wrong with that specific magazine, an occurrence not uncommon to any semi-auto pistol and easily fixed by acquiring additional magazines. In fact, all trainers will tell you to sort magazines and only carry those known to work perfectly.

Once the shooting started, there was only one smoke-stack malfunction where an empty case failed to clear the ejection port and was trapped between the closing slide and edge of the barrel hood. The shooter was a friend who was shooting left-handed, admitted to having hurt his wrist recently and suspected he had been less than aggressive in his shooting stance. Everything else went perfectly. We started with two boxes of Black Hills 230-grain jacketed hollow points before switching to frangible rounds.

Minimum group size at extended range is not the objective of a defensive handgun, so our shooting was done at ranges from 7 to 15 yards. Nevertheless, at 15 yards groups were easily held to 2 inches shooting relatively slowly and stayed around 4 to 6 inches when I hit the accelerator. Running the gun single action was easy, and that’s how the 845 is made to operate after the first shot-fired with the hammer back and a short trigger pull.

It’s difficult to design a gun with ergonomics that fit everyone. When the gun is required to operate in several different ways. i.e. single and double action, it’s impossible. Double-action pull will be noticeably heavier (and longer) because more functions are being performed by the same action.

When executing the long double-action trigger pull of the PT845, my trigger finger tends to slide to the bottom of the trigger away from the trigger’s pivot point where I get more leverage, thus making the trigger easier to pull. Unfortunately the bottom of the trigger guard slopes up as it joins the grip frame so my trigger finger drags along the inside of the trigger guard. This added resistance makes the trigger pull incredibly heavy and rather uncomfortable.

I think the reason for that upward sweep of the trigger guard is to allow for a higher grip on the frame, which helps control recoil. This may not be a problem for you. but for me to operate the gun in all its intended running modes, a redesigned trigger guard shape (including eliminating the hook at the front) would be helpful.

Other than that. I was quite pleased with the 845’s ergonomics and operating characteristics. It naturally pointed exactly where I looked, and even when firing the first shot double-action, all shots hit center mass or within a head-sized target at 15 yards. Even without the magazine in place, my hand fit comfortably on the grip frame, which meant I would have no problem shooting the pistol with the magazine removed. Still. I think the magazine extensions are a good idea for several reasons. First, they do facilitate a speed reload. Second, they help in rapidly removing a magazine that might fail to drop clear of the gun. And third, they are forgiving if your initial grab for the gun fails to achieve a perfect grip.

Overall. I think Taurus has done a good job on the new Model 845.1 can’t bring myself to say I think any polymer semi-auto is beautiful, but the top half of the 845 is cool, and the bottom half is functional. At the company’s suggested MSRP of $623. the gun has the makings of a winner.